Chapter 6

Deductions: Business Expenses

The Tax Formula:

(gross income)

→ MINUS deductions named in § 62

EQUALS (adjusted gross income (AGI))

→ MINUS (standard deduction or itemized deductions)

MINUS (deduction for “qualified business income”)

EQUALS (taxable income)

Compute income tax liability from tables in § 1(j) (indexed for inflation)

MINUS (credits against tax)

Our income tax system taxes only “net income.” The Code incorporates principles that prevent taxing as income the expenses of deriving that income. Section 162 provides a deduction for “all the ordinary and necessary expenses paid or incurred during the taxable year in carrying on any trade or business[.]” Read § 162(a).

The Code does not provide a definition of “trade or business.”92 The Supreme Court observed the following when it held that a full-time gambler was engaged in a “trade or business:”

Of course, not every income-producing and profit-making endeavor constitutes a trade or business. The income tax law, almost from the beginning, has distinguished between a business or trade, on the one hand, and “transactions entered into for profit but not connected with … business or trade,” on the other. See Revenue Act of 1916, § 5(a), Fifth, 39 Stat. 759. Congress “distinguished the broad range of income or profit producing activities from those satisfying the narrow category of trade or business.” We accept the fact that to be engaged in a trade or business, the taxpayer must be involved in the activity with continuity and regularity and that the taxpayer’s primary purpose for engaging in the activity must be for income or profit. A sporadic activity, a hobby, or an amusement diversion does not qualify.93

This excerpt informs that there is a distinction between a “trade or business” and “transactions entered into for profit but not connected with” a trade or business. For most taxpayers, investing fits this latter description. Moreover, there is another distinction between a “trade or business” and a hobby or amusement. The Code limits deductions for an activity “not engaged in for profit” to the gross income derived from the activity.94

Congress extended the principles of § 162(a) to “expenses for the production of income” when it added § 212 to the Code. However, expenses for the production of income – as contrasted with a trade or business – are not deductible “above the line.” § 62(a)(1). Moreover, no deduction for such expenses is allowed until 2026. § 67(g). For a trade or business expense to be deductible, § 162 requires that such expense be “ordinary and necessary.” Section 163(a) allows a deduction for interest paid or accrued. For taxpayers whose average gross receipts for the 3-year period ending with the immediately preceding tax year are $25,000,000 or more, § 448(c)(1), § 163(j) limits their interest deduction to the amount of their business interest income plus 30% of their trade or business income. § 163(j)(1 and 8).95 Section 165(a) allows a deduction for losses.

Section 162 allows a deduction only for expenses of “carrying on” a trade or business. Hence, the costs of searching for a business to purchase, pre-opening organization costs, etc. are not deductible. § 195. Taxpayer in such cases has no trade or business to “carry on.” On the other hand, an existing business that incurs the same expenses to expand its business may deduct them. Whether an existing business is seeking merely to expand or to enter a new trade or business “depends on the facts and circumstances of each case.”96

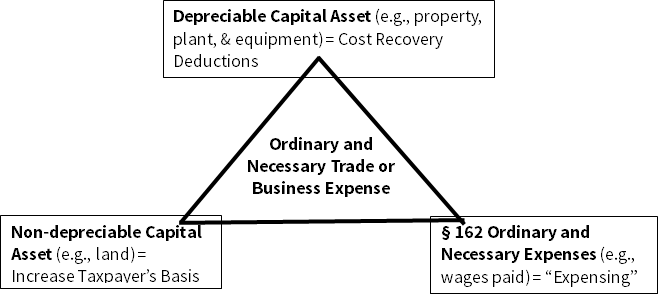

Taxpayer may “consume” (i.e., use up) what he buys to produce income in his trade or business at different rates. With regard to such consumption, consider the following possibilities:

Read § 263: Capital Expenditures: Notice that § 263(a)(1) denies a deduction for “amounts paid out” for “permanent improvements or betterments” to increase the value of taxpayer’s property. This does not mean that such amounts are never deductible. “Amounts paid out” are deductible as the improvement or betterment is consumed. See §§ 167, 168.

• Taxpayer may purchase an input and immediately consume it to make taxable income. Taxpayer purchases a tank of gasoline. We expect that such expenditures would be immediately deductible in full. We sometimes call this treatment “expensing.”

• Alternatively, taxpayer may purchase an input that he will consume more slowly and that will enable him to earn income for more than the current tax year. Nevertheless, the taxpayer will eventually “consume” that input. Taxpayer might purchase a machine that will enable him to generate income for the next ten years. Taxpayer has made an “investment” rather than an expenditure on an item that he immediately consumes. A mere change in the form in which taxpayer holds wealth is not a taxable event. We implement this principle by crediting taxpayer with basis equal to the money removed from his store of property rights to make the investment (i.e., purchase). Taxpayer (might) then consume only a part of the item that he purchased to generate income. What taxpayer consumes is no longer invested, and taxpayer has to that extent “de-invested” the amount consumed. The Code implements in several places a scheme that (theoretically) matches such consumption with the income that the expenditure generates. The Code permits a deduction for such partial consumption under the headings of depreciation, amortization, or more recently, cost recovery. Since such consumption represents a “deinvestment,” taxpayer must adjust his basis in the productive asset downward. We sometimes call this tax treatment of the purchase and use of a productive asset “capitalization.”

• The Code also implements such a matching of income with expenses when taxpayer derives gross income by selling from inventory. The Code has special rules that prohibit taxpayer from deferring recognition of income derived from sales from inventory by building up deductions through purchase of inventory in advance of the time he makes sales.

• Yet another possibility is that taxpayer may purchase an input that enables him to produce income but never in fact consumes that input, e.g., land. There should logically be no deduction – immediately or in the future – for such expenditures. Taxpayer will have a basis in such an asset, but can only recover it for income purposes upon sale of the asset. Some of these assets may not even be capable of sale, e.g., a legal education or other forms of human capital. We also call this tax treatment of the purchase and use of such an asset “capitalization.”

We usually think of disputes between a taxpayer and the Commissioner as binary in nature. The taxpayer argues one thing and the Commissioner argues the (only) opposite. For example, money that the taxpayer finds in a piano is or is not gross income; there are no other possibilities. Disputes concerning trade or business expenditures involve more possibilities. Initially expenditures are “ordinary and necessary” or they are not (binary). Cf. Gilliam, infra. Assuming an expenditure is an “ordinary and necessary” trade or business expense, it may be immediately deductible, it may never be deductible, or it may be deductible over an extended period during which it is consumed. In other words, there are three possibilities.

In the materials ahead, we very roughly consider the placement of expenditures into one group or another – whether expense or capital. Both the Commissioner and taxpayers are aware of the time value of money. Naturally, taxpayer usually wants to classify purchases of inputs that enable him to generate income in a manner that permits the earliest deduction. The Commissioner of course wants the opposite result. Try to determine the controlling principles by which to resolve these issues of classification.

I. Expense or Capital

The following cases involve the proper tax treatment of expenditures to purchase income-producing assets – whether immediately deductible, deductible over their useful life, or not deductible.

Welch v. Helvering, 290 U.S. 114 (1933)

MR. JUSTICE CARDOZO delivered the opinion of the Court.

The question to be determined is whether payments by a taxpayer, who is in business as a commission agent, are allowable deductions in the computation of his income if made to the creditors of a bankrupt corporation in an endeavor to strengthen his own standing and credit.

In 1922, petitioner was the secretary of the E.L. Welch Company, a Minnesota corporation, engaged in the grain business. The company was adjudged an involuntary bankrupt, and had a discharge from its debts. Thereafter the petitioner made a contract with the Kellogg Company to purchase grain for it on a commission. In order to reestablish his relations with customers whom he had known when acting for the Welch Company and to solidify his credit and standing, he decided to pay the debts of the Welch business so far as he was able. In fulfillment of that resolve, he made payments of substantial amounts during five successive years. … The Commissioner ruled that these payments were not deductible from income as ordinary and necessary expenses, but were rather in the nature of capital expenditures, an outlay for the development of reputation and goodwill. The Board of Tax Appeals sustained the action of the Commissioner and the Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit affirmed. The case is here on certiorari. …

We may assume that the payments to creditors of the Welch Company were necessary for the development of the petitioner’s business, at least in the sense that they were appropriate and helpful. [citation omitted]. He certainly thought they were, and we should be slow to override his judgment. But the problem is not solved when the payments are characterized as necessary. Many necessary payments are charges upon capital. There is need to determine whether they are both necessary and ordinary. Now, what is ordinary, though there must always be a strain of constancy within it, is nonetheless a variable affected by time and place and circumstance. “Ordinary” in this context does not mean that the payments must be habitual or normal in the sense that the same taxpayer will have to make them often. A lawsuit affecting the safety of a business may happen once in a lifetime. The counsel fees may be so heavy that repetition is unlikely. Nonetheless, the expense is an ordinary one because we know from experience that payments for such a purpose, whether the amount is large or small, are the common and accepted means of defense against attack. Cf. Kornhauser v. United States, 276 U.S. 145. The situation is unique in the life of the individual affected, but not in the life of the group, the community, of which he is a part. At such times, there are norms of conduct that help to stabilize our judgment, and make it certain and objective. The instance is not erratic, but is brought within a known type.

The line of demarcation is now visible between the case that is here and the one supposed for illustration. We try to classify this act as ordinary or the opposite, and the norms of conduct fail us. No longer can we have recourse to any fund of business experience, to any known business practice. Men do at times pay the debts of others without legal obligation or the lighter obligation imposed by the usages of trade or by neighborly amenities, but they do not do so ordinarily, not even though the result might be to heighten their reputation for generosity and opulence. Indeed, if language is to be read in its natural and common meaning [citations omitted], we should have to say that payment in such circumstances, instead of being ordinary, is in a high degree extraordinary. There is nothing ordinary in the stimulus evoking it, and none in the response. Here, indeed, as so often in other branches of the law, the decisive distinctions are those of degree, and not of kind. One struggles in vain for any verbal formula that will supply a ready touchstone. The standard set up by the statute is not a rule of law; it is rather a way of life. Life in all its fullness must supply the answer to the riddle.

The Commissioner of Internal Revenue resorted to that standard in assessing the petitioner’s income, and found that the payments in controversy came closer to capital outlays than to ordinary and necessary expenses in the operation of a business. His ruling has the support of a presumption of correctness, and the petitioner has the burden of proving it to be wrong. [citations omitted]. Unless we can say from facts within our knowledge that these are ordinary and necessary expenses according to the ways of conduct and the forms of speech prevailing in the business world, the tax must be confirmed. But nothing told us by this record or within the sphere of our judicial notice permits us to give that extension to what is ordinary and necessary. Indeed, to do so would open the door to many bizarre analogies. One man has a family name that is clouded by thefts committed by an ancestor. To add to his own standing he repays the stolen money, wiping off, it may be, his income for the year. The payments figure in his tax return as ordinary expenses. Another man conceives the notion that he will be able to practice his vocation with greater ease and profit if he has an opportunity to enrich his culture. Forthwith the price of his education becomes an expense of the business, reducing the income subject to taxation. There is little difference between these expenses and those in controversy here. Reputation and learning are akin to capital assets, like the goodwill of an old partnership. [citation omitted]. For many, they are the only tools with which to hew a pathway to success. The money spent in acquiring them is well and wisely spent. It is not an ordinary expense of the operation of a business.

Many cases in the federal courts deal with phases of the problem presented in the case at bar. To attempt to harmonize them would be a futile task. They involve the appreciation of particular situations at times with border-line conclusions. Typical illustrations are cited in the margin.97

The decree should be

Affirmed.

Notes and Questions:

1. The word “ordinary” as used in the phrase “ordinary and necessary” provides a line of demarcation between expenditures currently deductible and those that are either never deductible or deductible only over time, i.e., through depreciation, amortization, or cost recovery allowances.

• Since the expenses in Welch were not “ordinary,” the next question is whether taxpayer could deduct them over time through depreciation or amortization.

• What should be relevant in making this determination?

• Do you think that the expenses in Welch v. Helvering should be recoverable through depreciation or amortization allowances?

• In the second paragraph of the Court’s footnote, the Court cited several cases. Which expenditures should taxpayer be able to deduct over time through depreciation or amortization, and which should taxpayer not be able deduct at all – probably ever?

2. Consider these three rationales of the Court’s opinion: the expenditures were too personal to be deductible, were too bizarre to be ordinary, and were capital so not deductible.

• Personal: Welch felt a moral obligation, as many in Minnesota in such circumstances did at the time, to pay the corporation’s debts. In fact, Welch repaid the debts on the advice of bankers. This would seem to make business the motivation for repaying these debts.

• Bizarre: Others in Minnesota behaved the same way, i.e., repaid the debts of a bankrupt predecessor.

• Capital: The expenditures were no doubt capital in nature. However, they were arguably only an investment designed to generate income for a finite period. As such, the expenditures should be depreciable or amortizable.

• See Joel S. Newman, The Story of Welch: The Use (and Misuse) of the “Ordinary and Necessary” Test for Deducting Business Expenses, in Tax Stories 197-224 (Paul Caron ed., 2d ed. 2009).

3. What should be the tax consequences of making payments to create goodwill? What should be the tax consequences of maintaining or repairing goodwill?

4. By paying the debts of a bankrupt, no-longer-in-existence corporation, was Thomas Welch trying to create goodwill or to maintain or repair it? Whose goodwill?

• Consider: Conway Twitty (actually Harold Jenkins) was a famous country music singer. He formed a chain of fast food restaurants (“Twitty Burger, Inc.”). He persuaded seventy-five friends in the country music business to invest with him. The venture failed. Twitty was concerned about the effect of the adverse publicity on his country music career. He repaid the investors himself.

• If Twitty were trying to protect the reputation of Twitty Burger, the expenditures would surely have been nondeductible. Twitty Burger after all was defunct.

• The court found as a fact that one’s reputation in the country music business is very important.

• Deductible? See Harold L. Jenkins v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo 1983-667, 1983 WL 14653.

5. What should be the tax treatment of expenditures incurred to acquire property that has an indefinite useful life?

Woodward v. Commissioner, 397 U.S. 572 (1970)

MR. JUSTICE MARSHALL delivered the opinion of the Court.

….

Taxpayers owned or controlled a majority of the common stock of the Telegraph-Herald, an Iowa publishing corporation. The Telegraph-Herald was incorporated in 1901, and its charter was extended for 20-year periods in 1921 and 1941. On June 9, 1960, taxpayers voted their controlling share of the stock of the corporation in favor of a perpetual extension of the charter. A minority stockholder voted against the extension. Iowa law requires “those stockholders voting for such renewal . . . [to] purchase at its real value the stock voted against such renewal.” Iowa Code § 491.25 (1966).

Taxpayers attempted to negotiate purchase of the dissenting stockholder’s shares, but no agreement could be reached on the “real value” of those shares. Consequently, in 1962, taxpayers brought an action in state court to appraise the value of the minority stock interest. The trial court fixed a value, which was slightly reduced on appeal by the Iowa Supreme Court, [citations omitted]. In July, 1965, taxpayers purchased the minority stock interest at the price fixed by the court.

During 1963, taxpayers paid attorneys’, accountants’, and appraisers’ fees of over $25,000, for services rendered in connection with the appraisal litigation. On their 1963 federal income tax returns, taxpayers claimed deductions for these expenses, asserting that they were “ordinary and necessary expenses paid … for the management, conservation, or maintenance of property held for the production of income” deductible under § 212 … The Commissioner of Internal Revenue disallowed the deduction “because the fees represent capital expenditures incurred in connection with the acquisition of capital stock of a corporation.” The Tax Court sustained the Commissioner’s determination, with two dissenting opinions, and the Court of Appeals affirmed. We granted certiorari to resolve the conflict over the deductibility of the costs of appraisal proceedings between this decision and the decision of the Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit in United States v. Hilton Hotels Corp., [397 U.S. 580 (1970)]. We affirm.

Since the inception of the present federal income tax in 1913, capital expenditures have not been deductible. See § 263. Such expenditures are added to the basis of the capital asset with respect to which they are incurred, and are taken into account for tax purposes either through depreciation or by reducing the capital gain (or increasing the loss) when the asset is sold. If an expense is capital, it cannot be deducted as “ordinary and necessary,” either as a business expense under § 162 of the Code or as an expense of “management, conservation, or maintenance” under § 212.98

It has long been recognized, as a general matter, that costs incurred in the acquisition or disposition of a capital asset are to be treated as capital expenditures. The most familiar example of such treatment is the capitalization of brokerage fees for the sale or purchase of securities, as explicitly provided by a longstanding Treasury regulation, Reg. § 1.263(a)-2(e), and as approved by this Court in Helvering v. Winmill, 305 U.S. 79 (1938), and Spreckels v. Commissioner, 315 U.S. 626 (1942). The Court recognized that brokers’ commissions are “part of the acquisition cost of the securities,” Helvering v. Winmill, supra, at 305 U.S. 84, and relied on the Treasury regulation, which had been approved by statutory reenactment, to deny deductions for such commissions even to a taxpayer for whom they were a regular and recurring expense in his business of buying and selling securities.

The regulations do not specify other sorts of acquisition costs, but rather provide generally that “[t]he cost of acquisition … of … property having a useful life substantially beyond the taxable year” is a capital expenditure. Reg. § 1.263(a)-2(a). Under this general provision, the courts have held that legal, brokerage, accounting, and similar costs incurred in the acquisition or disposition of such property are capital expenditures. See, e.g., Spangler v. Commissioner, 323 F.2d 913, 921 (C.A. 9th Cir.1963); United States v. St. Joe Paper Co., 284 F.2d 430, 432 (C.A. 5th Cir.1960). [citation omitted]. The law could hardly be otherwise, for such ancillary expenses incurred in acquiring or disposing of an asset are as much part of the cost of that asset as is the price paid for it.

More difficult questions arise with respect to another class of capital expenditures, those incurred in “defending or perfecting title to property.” Reg. § 1.263(a)-2(c). In one sense, any lawsuit brought against a taxpayer may affect his title to property – money or other assets subject to lien. The courts, not believing that Congress meant all litigation expenses to be capitalized, have created the rule that such expenses are capital in nature only where the taxpayer’s “primary purpose” in incurring them is to defend or perfect title. See, e.g., Rassenfoss v. Commissioner, 158 F.2d 764 (C.A. 7th Cir.1946); Industrial Aggregate Co. v. United States, 284 F.2d 639, 645 (C.A. 8th Cir.1960). This test hardly draws a bright line, and has produced a melange of decisions which, as the Tax Court has noted, “[i]t would be idle to suggest … can be reconciled.” Ruoff v. Commissioner, 30 T.C. 204, 208 (1958).

Taxpayers urge that this “primary purpose” test, developed in the context of cases involving the costs of defending property, should be applied to costs incurred in acquiring or disposing of property as well. And if it is so applied, they argue, the costs here in question were properly deducted, since the legal proceedings in which they were incurred did not directly involve the question of title to the minority stock, which all agreed was to pass to taxpayers, but rather was concerned solely with the value of that stock.

We agree with the Tax Court and the Court of Appeals that the “primary purpose” test has no application here. That uncertain and difficult test may be the best that can be devised to determine the tax treatment of costs incurred in litigation that may affect a taxpayer’s title to property more or less indirectly, and that thus calls for a judgment whether the taxpayer can fairly be said to be “defending or perfecting title.” Such uncertainty is not called for in applying the regulation that makes the “cost of acquisition” of a capital asset a capital expense. In our view, application of the latter regulation to litigation expenses involves the simpler inquiry whether the origin of the claim litigated is in the process of acquisition itself.

A test based upon the taxpayer’s “purpose” in undertaking or defending a particular piece of litigation would encourage resort to formalism and artificial distinctions. For instance, in this case, there can be no doubt that legal, accounting, and appraisal costs incurred by taxpayers in negotiating a purchase of the minority stock would have been capital expenditures. See Atzingen-Whitehouse Dairy Inc. v. Commissioner, 36 T.C. 173 (1961). Under whatever test might be applied, such expenses would have clearly been “part of the acquisition cost” of the stock. Helvering v. Winmill, supra. Yet the appraisal proceeding was no more than the substitute that state law provided for the process of negotiation as a means of fixing the price at which the stock was to be purchased. Allowing deduction of expenses incurred in such a proceeding, merely on the ground that title was not directly put in question in the particular litigation, would be anomalous.

Further, a standard based on the origin of the claim litigated comports with this Court’s recent ruling on the characterization of litigation expenses for tax purposes in United States v. Gilmore, 372 U.S. 39 (1963). This Court there held that the expense of defending a divorce suit was a nondeductible personal expense, even though the outcome of the divorce case would affect the taxpayer’s property holdings, and might affect his business reputation. The Court rejected a test that looked to the consequences of the litigation, and did not even consider the taxpayer’s motives or purposes in undertaking defense of the litigation, but rather examined the origin and character of the claim against the taxpayer, and found that the claim arose out of the personal relationship of marriage.

The standard here pronounced may, like any standard, present borderline cases, in which it is difficult to determine whether the origin of particular litigation lies in the process of acquisition. This is not such a borderline case. Here state law required taxpayers to “purchase” the stock owned by the dissenter. In the absence of agreement on the price at which the purchase was to be made, litigation was required to fix the price. Where property is acquired by purchase, nothing is more clearly part of the process of acquisition than the establishment of a purchase price.99 Thus, the expenses incurred in that litigation were properly treated as part of the cost of the stock that the taxpayers acquired.

Affirmed.

Notes and Questions:

1. Will taxpayers be permitted to claim depreciation or amortization deductions for the expenditures in question? Why or why not?

2. This case arose under § 212, not § 162. Section 212 deductions are “miscellaneous deductions” under § 67 and are disallowed until tax year 2026. § 67(g). However, § 162 and § 212 are in pari materia with each other. See the Court’s first footnote.

3. M owned certain real estate in Memphis, Tennessee. In 2018, M entered into contracts to lease the properties for a term of fifty years, and in 2018 paid commissions and fees to a real estate broker and attorney for services in obtaining the contracts.

• For tax purposes, how should M treat the real estate brokerage commissions?

• See Renwick v. United States, 87 F.2d 123, 125 (7th Cir. 1936); Meyran v. Commissioner, 63 F.2d 986 (3d Cir. 1933).

Start-up Expenses of a Business: No deduction is permitted for the start-up expenses of a proprietorship (§ 195), corporation (§ 248), or partnership (§ 709) – except as specifically provided. What would be the rationale of this treatment?

4. S owned stock in several different companies. He sold 100 shares of IBM stock for a nice profit and incurred a brokerage commission of $500. For tax purposes, how should S treat the brokerage commissions?

• Does it make any difference whether S treats the brokerage commission as an ordinary and necessary expense of investment activity or as a decrease in his “amount realized?”

• See Spreckels v. Commissioner, 315 U.S. 626 (1942); cf. 67(g).

5. W purchased the IBM stock that S sold, supra. W incurred a brokerage commission of $500. For tax purposes, how should W treat the brokerage commissions?

• Does it make any difference whether W treats the brokerage commission as an ordinary and necessary expense of investment activity or as an increase in his basis?

• See Helvering v. Winmill, 305 U.S. 79 (1938).

A. Expense or Capital: Cost of Constructing a Tangible Capital Asset

What should be the tax treatment of the cost of taxpayer’s self-construction of a productive asset for it to use in its own business? Should there be a parallel between such activity and the tax treatment we accord imputed income?

Commissioner v. Idaho Power Co., 418 U.S. 1 (1974)

MR. JUSTICE BLACKMUN delivered the opinion of the Court.

This case presents the sole issue whether, for federal income tax purposes, a taxpayer is entitled to a deduction from gross income, under [I.R.C.] § 167(a) …100 … for depreciation on equipment the taxpayer owns and uses in the construction of its own capital facilities, or whether the capitalization provision of § 263(a)(1) of the Code101 …, bars the deduction.

The taxpayer claimed the deduction, but the Commissioner … disallowed it. The Tax Court … upheld the Commissioner’s determination. The United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, declining to follow a Court of Claims decision, Southern Natural Gas Co. v. United States, 412 F.2d 1222, 1264-1269 (1969), reversed. We granted certiorari in order to resolve the apparent conflict between the Court of Claims and the Court of Appeals.

I

… The taxpayer-respondent, Idaho Power Company, … is a public utility engaged in the production, transmission, distribution, and sale of electric energy. The taxpayer keeps its books and files its federal income tax returns on the calendar year accrual basis. The tax years at issue are 1962 and 1963.

For many years, the taxpayer has used its own equipment and employees in the construction of improvements and additions to its capital facilities. . The major work has consisted of transmission lines, transmission switching stations, distribution lines, distribution stations, and connecting facilities.

During 1962 and 1963, the tax years in question, taxpayer owned and used in its business a wide variety of automotive transportation equipment, including passenger cars, trucks of all descriptions, power-operated equipment, and trailers. Radio communication devices were affixed to the equipment, and were used in its daily operations. The transportation equipment was used in part for operation and maintenance and in part for the construction of capital facilities having a useful life of more than one year.

….

… [O]n its books, in accordance with Federal Power Commission-Idaho Public Utilities Commission prescribed methods, the taxpayer capitalized the construction-related depreciation, but, for income tax purposes, that depreciation increment was [computed on a composite life of ten years under straight-line and declining balance methods, and] claimed as a deduction under § 167(a).

Upon audit, the Commissioner … disallowed the deduction for the construction-related depreciation. He ruled that that depreciation was a nondeductible capital expenditure to which § 263(a)(1) had application. He added the amount of the depreciation so disallowed to the taxpayer’s adjusted basis in its capital facilities, and then allowed a deduction for an appropriate amount of depreciation on the addition, computed over the useful life (30 years or more) of the property constructed. A deduction for depreciation of the transportation equipment to the extent of its use in day-to-day operation and maintenance was also allowed. The result of these adjustments was the disallowance of depreciation, as claimed by the taxpayer on its returns, in the net amounts of $140,429.75 and $96,811.95 for 1962 and 1963, respectively. This gave rise to asserted deficiencies in taxpayer’s income taxes for those two years of $73,023.47 and $50,342.21.

The Tax Court agreed with the [Commissioner.] …

The Court of Appeals, on the other hand, perceived in the … Code … the presence of a liberal congressional policy toward depreciation, the underlying theory of which is that capital assets used in business should not be exhausted without provision for replacement. The court concluded that a deduction expressly enumerated in the Code, such as that for depreciation, may properly be taken, and that “no exception is made should it relate to a capital item.” Section 263(a)(1) … was found not to be applicable, because depreciation is not an “amount paid out,” as required by that section. …

The taxpayer asserts that its transportation equipment is used in its “trade or business,” and that depreciation thereon is therefore deductible under § 167(a)(1) … The Commissioner concedes that § 167 may be said to have a literal application to depreciation on equipment used in capital construction,102 but contends that the provision must be read in light of § 263(a)(1), which specifically disallows any deduction for an amount “paid out for new buildings or for permanent improvements or betterments.” He argues that § 263 takes precedence over § 167 by virtue of what he calls the “priority-ordering” terms (and what the taxpayer describes as “housekeeping” provisions) of § 161 of the Code103 … and that sound principles of accounting and taxation mandate the capitalization of this depreciation.

It is worth noting the various items that are not at issue here. … There is no disagreement as to the allocation of depreciation between construction and maintenance. The issue thus comes down primarily to a question of timing, … that is, whether the construction-related depreciation is to be amortized and deducted over the shorter life of the equipment or, instead, is to be amortized and deducted over the longer life of the capital facilities constructed.

II

Our primary concern is with the necessity to treat construction-related depreciation in a manner that comports with accounting and taxation realities. Over a period of time, a capital asset is consumed and, correspondingly over that period, its theoretical value and utility are thereby reduced. Depreciation is an accounting device which recognizes that the physical consumption of a capital asset is a true cost, since the asset is being depleted.104 As the process of consumption continues, and depreciation is claimed and allowed, the asset’s adjusted income tax basis is reduced to reflect the distribution of its cost over the accounting periods affected. The Court stated in Hertz Corp. v. United States, 364 U.S. 122, 126 (1960): [T]he purpose of depreciation accounting is to allocate the expense of using an asset to the various periods which are benefited by that asset. [citations omitted]. When the asset is used to further the taxpayer’s day-to-day business operations, the periods of benefit usually correlate with the production of income. Thus, to the extent that equipment is used in such operations, a current depreciation deduction is an appropriate offset to gross income currently produced. It is clear, however, that different principles are implicated when the consumption of the asset takes place in the construction of other assets that, in the future, will produce income themselves. In this latter situation, the cost represented by depreciation does not correlate with production of current income. Rather, the cost, although certainly presently incurred, is related to the future and is appropriately allocated as part of the cost of acquiring an income-producing capital asset.

The Court of Appeals opined that the purpose of the depreciation allowance under the Code was to provide a means of cost recovery, Knoxville v. Knoxville Water Co., 212 U.S. 1, 13-14 (1909), and that this Court’s decisions, e.g., Detroit Edison Co. v. Commissioner, 319 U.S. 98, 101 (1943), endorse a theory of replacement through “a fund to restore the property.” Although tax-free replacement of a depreciating investment is one purpose of depreciation accounting, it alone does not require the result claimed by the taxpayer here. Only last Term, in United States v. Chicago, B. & Q. R. Co., 412 U.S. 401 (1973), we rejected replacement as the strict and sole purpose of depreciation:

“Whatever may be the desirability of creating a depreciation reserve under these circumstances, as a matter of good business and accounting practice, the answer is … [depreciation] reflects the cost of an existing capital asset, not the cost of a potential replacement.”

Id. at 415.

Even were we to look to replacement, it is the replacement of the constructed facilities, not the equipment used to build them, with which we would be concerned. If the taxpayer now were to decide not to construct any more capital facilities with its own equipment and employees, it, in theory, would have no occasion to replace its equipment to the extent that it was consumed in prior construction.

Accepted accounting practice105 and established tax principles require the capitalization of the cost of acquiring a capital asset. In Woodward v. Commissioner, 397 U.S. 572, 575 (1970), the Court observed: “It has long been recognized, as a general matter, that costs incurred in the acquisition … of a capital asset are to be treated as capital expenditures.” This principle has obvious application to the acquisition of a capital asset by purchase, but it has been applied, as well, to the costs incurred in a taxpayer’s construction of capital facilities. [citations omitted].

There can be little question that other construction-related expense items, such as tools, materials, and wages paid construction workers, are to be treated as part of the cost of acquisition of a capital asset. The taxpayer does not dispute this. Of course, reasonable wages paid in the carrying on of a trade or business qualify as a deduction from gross income. § 162(a)(1) … But when wages are paid in connection with the construction or acquisition of a capital asset, they must be capitalized, and are then entitled to be amortized over the life of the capital asset so acquired. [citations omitted].

Construction-related depreciation is not unlike expenditures for wages for construction workers. The significant fact is that the exhaustion of construction equipment does not represent the final disposition of the taxpayer’s investment in that equipment; rather, the investment in the equipment is assimilated into the cost of the capital asset constructed. Construction-related depreciation on the equipment is not an expense to the taxpayer of its day-to-day business. It is, however, appropriately recognized as a part of the taxpayer’s cost or investment in the capital asset. … By the same token, this capitalization prevents the distortion of income that would otherwise occur if depreciation properly allocable to asset acquisition were deducted from gross income currently realized. [citations omitted].

An additional pertinent factor is that capitalization of construction-related depreciation by the taxpayer who does its own construction work maintains tax parity with the taxpayer who has its construction work done by an independent contractor. The depreciation on the contractor’s equipment incurred during the performance of the job will be an element of cost charged by the contractor for his construction services, and the entire cost, of course, must be capitalized by the taxpayer having the construction work performed. The Court of Appeals’ holding would lead to disparate treatment among taxpayers, because it would allow the firm with sufficient resources to construct its own facilities and to obtain a current deduction, whereas another firm without such resources would be required to capitalize its entire cost, including depreciation charged to it by the contractor.

….

[Taxpayer argued that the language of § 263(a)(1), which denies a current deduction for “new buildings or for permanent improvements or betterments,” only applies when taxpayer has “paid out” an “amount.” Depreciation, taxpayer argued, represented a decrease in value – not an “amount … paid out.” The Court rejected this limitation on § 263’s applicability. Instead, the Court accepted the IRS’s administrative construction of that phrase to mean “cost incurred.” Construction-related depreciation is such a cost.] In acquiring the transportation equipment, taxpayer “paid out” the equipment’s purchase price; depreciation is simply the means of allocating the payment over the various accounting periods affected. As the Tax Court stated in Brooks v. Commissioner, 50 T.C. at 935, “depreciation – inasmuch as it represents a using up of capital – is as much an expenditure’ as the using up of labor or other items of direct cost.”

Finally, the priority-ordering directive of § 161 – or, for that matter, … § 261106 – requires that the capitalization provision of § 263(a) take precedence, on the facts here, over § 167(a). Section 161 provides that deductions specified in Part VI of Subchapter B of the Income Tax Subtitle of the Code are “subject to the exceptions provided in part IX.” Part VI includes § 167, and Part IX includes § 263. The clear import of § 161 is that, with stated exceptions set forth either in § 263 itself or provided for elsewhere (as, for example, in § 404, relating to pension contributions), none of which is applicable here, an expenditure incurred in acquiring capital assets must be capitalized even when the expenditure otherwise might be deemed deductible under Part VI.

The Court of Appeals concluded, without reference to § 161, that § 263 did not apply to a deduction, such as that for depreciation of property used in a trade or business, allowed by the Code even though incurred in the construction of capital assets. We think that the court erred in espousing so absolute a rule, and it obviously overlooked the contrary direction of § 161. To the extent that reliance was placed on the congressional intent, in the evolvement of the 1954 Code, to provide for “liberalization of depreciation,” H.R. Rep. No. 1337, 83d Cong., 2d Sess., 22 (1954), that reliance is misplaced. The House Report also states that the depreciation provisions would “give the economy added stimulus and resilience without departing from realistic standards of depreciation accounting.” Id. at 24. To be sure, the 1954 Code provided for new and accelerated methods for depreciation, resulting in the greater depreciation deductions currently available. These changes, however, relate primarily to computation of depreciation. Congress certainly did not intend that provisions for accelerated depreciation should be construed as enlarging the class of depreciable assets to which § 167(a) has application or as lessening the reach of § 263(a). [citation omitted].

We hold that the equipment depreciation allocable to taxpayer’s construction of capital facilities is to be capitalized.

The judgment of the Court of Appeals is reversed.

It is so ordered.

MR. JUSTICE DOUGLAS, dissenting. [omitted].

Notes and Questions:

1. The Court noted that the net of taxpayer’s disallowed depreciation deductions was $140,429.75 and $96,811.95 for 1962 and 1963 respectively. The useful life of the items that taxpayer was constructing was three or more times as long as the useful life of the equipment it used to construct those items. This case is about the fraction of the figures noted here that taxpayer may deduct – after the item is placed in service.

• Assuming straight-line depreciation of the equipment, the difference in the parties’ treatment of a depreciation deduction was the difference between 1/10 and 1/30 of 1/10 of the cost of equipment.

Taxpayer’s books and taxpayer’s tax books: Distinguish between taxpayer’s books (“its books”) and taxpayer’s tax books (“for federal income tax purposes”). For what purposes does taxpayer keep each set of books? Do you think that they would ever be different? Why or why not?

2. Why do we allow deductions for depreciation? Is it that –

• “capital assets used in business should not be exhausted without provision for replacement”?

• physical consumption of a capital asset reduces its value and utility, and a depreciation deduction implicitly recognizes this.

• obsolescence may reduce the value and utility of an asset, even if the asset is not exhausted and could still function, e.g., a twenty-year old personal computer? See the Court’s fifth footnote.

• a depreciation deduction in effect allocates the expense of using an asset to the various periods which are benefitted by that asset?

How do these rationales apply to a case where taxpayer consumes depreciable assets in the construction of income-producing capital assets?

3. Aside from the Code’s mandate in § 1016(a)(2), why must a taxpayer reduce its adjusted basis in an asset subject to depreciation?

4. How did the Court’s treatment of depreciation in this case prevent the distortion of income?

5. Why might Congress want to mismatch the timing of income and expenses and thereby distort income?

Sections 161 and 261: How does the language of §§ 161 and 261 create an ordering rule? What deductions do §§ 262 to 280H create?

6. The case demonstrates again how important the time value of money is.

B. Expense or Capital: Cost of “Constructing” an Intangible Capital Asset

What should be the rule when taxpayer self-creates an intangible asset that it can use to generate taxable income? Are there any (obvious) difficulties to applying the rule of Idaho Power to such a situation? Identify what taxpayer in INDOPCO argued was the rule of Lincoln Savings? Would taxpayer’s statement of that rule solve those difficulties?

INDOPCO, Inc. v. Commissioner, 503 U.S. 79 (1992)

JUSTICE BLACKMUN delivered the opinion of the Court.

In this case we must decide whether certain professional expenses incurred by a target corporation in the course of a friendly takeover are deductible by that corporation as “ordinary and necessary” business expenses under § 162(a) of the Internal Revenue Code.

I

… Petitioner INDOPCO, Inc., formerly named National Starch and Chemical Corporation and hereinafter referred to as National Starch, … manufactures and sells adhesives, starches, and specialty chemical products. In October 1977, representatives of Unilever United States, Inc., … (Unilever), expressed interest in acquiring National Starch, which was one of its suppliers, through a friendly transaction. National Starch at the time had outstanding over 6,563,000 common shares held by approximately 3,700 shareholders. The stock was listed on the New York Stock Exchange. Frank and Anna Greenwall were the corporation’s largest shareholders and owned approximately 14.5% of the common. The Greenwalls, getting along in years and concerned about their estate plans, indicated that they would transfer their shares to Unilever only if a transaction tax free for them could be arranged.

Lawyers representing both sides devised a “reverse subsidiary cash merger” that they felt would satisfy the Greenwalls’ concerns. Two new entities would be created – National Starch and Chemical Holding Corp. (Holding), a subsidiary of Unilever, and NSC Merger, Inc., a subsidiary of Holding that would have only a transitory existence. …

In November 1977, National Starch’s directors were formally advised of Unilever’s interest and the proposed transaction. At that time, Debevoise, Plimpton, Lyons & Gates, National Starch’s counsel, told the directors that under Delaware law they had a fiduciary duty to ensure that the proposed transaction would be fair to the shareholders. National Starch thereupon engaged the investment banking firm of Morgan Stanley & Co., Inc., to evaluate its shares, to render a fairness opinion, and generally to assist in the event of the emergence of a hostile tender offer.

Although Unilever originally had suggested a price between $65 and $70 per share, negotiations resulted in a final offer of $73.50 per share, a figure Morgan Stanley found to be fair. Following approval by National Starch’s board and the issuance of a favorable private ruling from the Internal Revenue Service that the transaction would be tax free … for those National Starch shareholders who exchanged their stock for Holding preferred, the transaction was consummated in August 1978.107

Morgan Stanley charged National Starch a fee of $2,200,000, along with $7,586 for out-of-pocket expenses and $18,000 for legal fees. The Debevoise firm charged National Starch $490,000, along with $15,069 for out-of-pocket expenses. National Starch also incurred expenses aggregating $150,962 for miscellaneous items – such as accounting, printing, proxy solicitation, and Securities and Exchange Commission fees – in connection with the transaction. No issue is raised as to the propriety or reasonableness of these charges.

On its federal income tax return … National Starch claimed a deduction for the $2,225,586 paid to Morgan Stanley, but did not deduct the $505,069 paid to Debevoise or the other expenses. Upon audit, the Commissioner of Internal Revenue disallowed the claimed deduction and issued a notice of deficiency. Petitioner sought redetermination in the United States Tax Court, asserting, however, not only the right to deduct the investment banking fees and expenses but, as well, the legal and miscellaneous expenses incurred.

The Tax Court, in an unreviewed decision, ruled that the expenditures were capital in nature and therefore not deductible under § 162(a) in the 1978 return as “ordinary and necessary expenses.” The court based its holding primarily on the long-term benefits that accrued to National Starch from the Unilever acquisition. The United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit affirmed, upholding the Tax Court’s findings that “both Unilever’s enormous resources and the possibility of synergy arising from the transaction served the long-term betterment of National Starch.” In so doing, the Court of Appeals rejected National Starch’s contention that, because the disputed expenses did not “create or enhance … a separate and distinct additional asset,” see Commissioner v. Lincoln Savings & Loan Assn., 403 U.S. 345, 354 (1971), they could not be capitalized and therefore were deductible under § 162(a). We granted certiorari to resolve a perceived conflict on the issue among the Courts of Appeals.108

II

Section 162(a) … allows the deduction of “all the ordinary and necessary expenses paid or incurred during the taxable year in carrying on any trade or business.” In contrast, § 263 … allows no deduction for a capital expenditure – an “amount paid out for new buildings or for permanent improvements or betterments made to increase the value of any property or estate.” § 263(a)(1). The primary effect of characterizing a payment as either a business expense or a capital expenditure concerns the timing of the taxpayer’s cost recovery: While business expenses are currently deductible, a capital expenditure usually is amortized and depreciated over the life of the relevant asset, or, where no specific asset or useful life can be ascertained, is deducted upon dissolution of the enterprise. See 26 U.S.C. §§ 167(a) and 336(a); Reg. § 1.167(a) (1991). Through provisions such as these, the Code endeavors to match expenses with the revenues of the taxable period to which they are properly attributable, thereby resulting in a more accurate calculation of net income for tax purposes. See, e. g., Commissioner v. Idaho Power Co., 418 U.S. 1, 16 (1974); Ellis Banking Corp. v. Commissioner, 688 F.2d 1376, 1379 (CA ll 1982), cert. denied, 463 U.S. 1207 (1983).

In exploring the relationship between deductions and capital expenditures, this Court has noted the “familiar rule” that “an income tax deduction is a matter of legislative grace and that the burden of clearly showing the right to the claimed deduction is on the taxpayer.” Interstate Transit Lines v. Commissioner, 319 U.S. 590, 593 (1943); Deputy v. Du Pont, 308 U.S. 488, 493 (1940); New Colonial Ice Co. v. Helvering, 292 U.S. 435, 440 (1934). The notion that deductions are exceptions to the norm of capitalization finds support in various aspects of the Code. Deductions are specifically enumerated and thus are subject to disallowance in favor of capitalization. See §§ 161 and 261. Nondeductible capital expenditures, by contrast, are not exhaustively enumerated in the Code; rather than providing a “complete list of nondeductible expenditures,” Lincoln Savings, 403 U.S. at 358, § 263 serves as a general means of distinguishing capital expenditures from current expenses. See Commissioner v. Idaho Power Co., 418 U.S. at 16. For these reasons, deductions are strictly construed and allowed only “as there is a clear provision therefor.” New Colonial Ice Co. v. Helvering, 292 U.S., at 440; Deputy v. Du Pont, 308 U.S., at 493.

The Court also has examined the interrelationship between the Code’s business expense and capital expenditure provisions. In so doing, it has had occasion to parse § 162(a) and explore certain of its requirements. For example, in Lincoln Savings, we determined that, to qualify for deduction under § 162(a), “an item must (1) be ‘paid or incurred during the taxable year,’ (2) be for ‘carrying on any trade or business,’ (3) be an ‘expense,’ (4) be a ‘necessary’ expense, and (5) be an ‘ordinary’ expense.” 403 U.S. at 352. See also Commissioner v. Tellier, 383 U.S. 687, 689 (1966) (the term “necessary” imposes “only the minimal requirement that the expense be ‘appropriate and helpful’ for ‘the development of the [taxpayer’s] business,’” quoting Welch v. Helvering, 290 U.S. 111, 113 (1933)); Deputy v. Du Pont, 308 U.S. at 495 (to qualify as “ordinary,” the expense must relate to a transaction “of common or frequent occurrence in the type of business involved”). The Court has recognized, however, that the “decisive distinctions” between current expenses and capital expenditures “are those of degree and not of kind,” Welch v. Helvering, 290 U.S. at 114, and that because each case “turns on its special facts,” Deputy v. Du Pont, 308 U.S. at 496, the cases sometimes appear difficult to harmonize. See Welch v. Helvering, 290 U.S. at 116.

National Starch contends that the decision in Lincoln Savings changed these familiar backdrops and announced an exclusive test for identifying capital expenditures, a test in which “creation or enhancement of an asset” is a prerequisite to capitalization, and deductibility under § 162(a) is the rule rather than the exception. We do not agree, for we conclude that National Starch has overread Lincoln Savings.

In Lincoln Savings, we were asked to decide whether certain premiums, required by federal statute to be paid by a savings and loan association to the Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation (FSLIC), were ordinary and necessary expenses under § 162(a), as Lincoln Savings argued and the Court of Appeals had held, or capital expenditures under § 263, as the Commissioner contended. We found that the “additional” premiums, the purpose of which was to provide FSLIC with a secondary reserve fund in which each insured institution retained a pro rata interest recoverable in certain situations, “serv[e] to create or enhance for Lincoln what is essentially a separate and distinct additional asset.” 403 U.S. at 354. “[A]s an inevitable consequence,” we concluded, “the payment is capital in nature and not an expense, let alone an ordinary expense, deductible under § 162(a).” Ibid.

Lincoln Savings stands for the simple proposition that a taxpayer’s expenditure that “serves to create or enhance … a separate and distinct” asset should be capitalized under § 263. It by no means follows, however, that only expenditures that create or enhance separate and distinct assets are to be capitalized under § 263. We had no occasion in Lincoln Savings to consider the tax treatment of expenditures that, unlike the additional premiums at issue there, did not create or enhance a specific asset, and thus the case cannot be read to preclude capitalization in other circumstances. In short, Lincoln Savings holds that the creation of a separate and distinct asset well may be a sufficient, but not a necessary, condition to classification as a capital expenditure. See General Bancshares Corp. v. Commissioner, 326 F.2d 712, 716 (CA8) (although expenditures may not “resul[t] in the acquisition or increase of a corporate asset, … these expenditures are not, because of that fact, deductible as ordinary and necessary business expenses”), cert. denied, 379 U.S. 832 (1964).

Nor does our statement in Lincoln Savings, 403 U.S. at 354, that “the presence of an ensuing benefit that may have some future aspect is not controlling” prohibit reliance on future benefit as a means of distinguishing an ordinary business expense from a capital expenditure.109 Although the mere presence of an incidental future benefit – “some future aspect” – may not warrant capitalization, a taxpayer’s realization of benefits beyond the year in which the expenditure is incurred is undeniably important in determining whether the appropriate tax treatment is immediate deduction or capitalization. See United States v. Mississippi Chemical Corp., 405 U.S. 298, 310 (1972) (expense that “is of value in more than one taxable year” is a nondeductible capital expenditure); Central Texas Savings & Loan Assn. v. United States, 731 F.2d 1181, 1183 (CA5 1984) (“While the period of the benefits may not be controlling in all cases, it nonetheless remains a prominent, if not predominant, characteristic of a capital item”). Indeed, the text of the Code’s capitalization provision, § 263(a)(1), which refers to “permanent improvements or betterments,” itself envisions an inquiry into the duration and extent of the benefits realized by the taxpayer.

III

In applying the foregoing principles to the specific expenditures at issue in this case, we conclude that National Starch has not demonstrated that the investment banking, legal, and other costs it incurred in connection with Unilever’s acquisition of its shares are deductible as ordinary and necessary business expenses under § 162(a).

Although petitioner attempts to dismiss the benefits that accrued to National Starch from the Unilever acquisition as “entirely speculative” or “merely incidental,” the Tax Court’s and the Court of Appeals’ findings that the transaction produced significant benefits to National Starch that extended beyond the tax year in question are amply supported by the record. For example, in commenting on the merger with Unilever, National Starch’s 1978 “Progress Report” observed that the company would “benefit greatly from the availability of Unilever’s enormous resources, especially in the area of basic technology.” (Unilever “provides new opportunities and resources”). Morgan Stanley’s report to the National Starch board concerning the fairness to shareholders of a possible business combination with Unilever noted that National Starch management “feels that some synergy may exist with the Unilever organization given a) the nature of the Unilever chemical, paper, plastics and packaging operations … and b) the strong consumer products orientation of Unilever United States, Inc.”

In addition to these anticipated resource-related benefits, National Starch obtained benefits through its transformation from a publicly held, freestanding corporation into a wholly owned subsidiary of Unilever. The Court of Appeals noted that National Starch management viewed the transaction as “‘swapping approximately 3500 shareholders for one.’” Following Unilever’s acquisition of National Starch’s outstanding shares, National Starch was no longer subject to what even it terms the “substantial” shareholder-relations expenses a publicly traded corporation incurs, including reporting and disclosure obligations, proxy battles, and derivative suits. The acquisition also allowed National Starch, in the interests of administrative convenience and simplicity, to eliminate previously authorized but unissued shares of preferred and to reduce the total number of authorized shares of common from 8,000,000 to 1,000.

Courts long have recognized that expenses such as these, “‘incurred for the purpose of changing the corporate structure for the benefit of future operations are not ordinary and necessary business expenses.’” General Bancshares Corp. v. Commissioner, 326 F.2d, at 715 (quoting Farmers Union Corp. v. Commissioner, 300 F.2d 197, 200 (CA9), cert. denied, 371 U.S. 861 (1962)). See also B. Bittker & J. Eustice, Federal Income Taxation of Corporations and Shareholders 5-33 to 5-36 (5th ed. 1987) (describing “well-established rule” that expenses incurred in reorganizing or restructuring corporate entity are not deductible under § 162(a)). Deductions for professional expenses thus have been disallowed in a wide variety of cases concerning changes in corporate structure.110 Although support for these decisions can be found in the specific terms of § 162(a), which require that deductible expenses be “ordinary and necessary” and incurred “in carrying on any trade or business,”111 courts more frequently have characterized an expenditure as capital in nature because “the purpose for which the expenditure is made has to do with the corporation’s operations and betterment, sometimes with a continuing capital asset, for the duration of its existence or for the indefinite future or for a time somewhat longer than the current taxable year.” General Bancshares Corp. v. Commissioner, 326 F.2d at 715. See also Mills Estate, Inc. v. Commissioner, 206 F.2d 244, 246 (CA2 1953). The rationale behind these decisions applies equally to the professional charges at issue in this case.

IV

The expenses that National Starch incurred in Unilever’s friendly takeover do not qualify for deduction as “ordinary and necessary” business expenses under § 162(a). The fact that the expenditures do not create or enhance a separate and distinct additional asset is not controlling; the acquisition-related expenses bear the indicia of capital expenditures and are to be treated as such.

The judgment of the Court of Appeals is affirmed.

It is so ordered.

Notes and Questions:

1. The INDOPCO decision was not well received in the business community. Why not?

• Should taxpayer in INDOPCO amortize the intangible that it purchased? – over what period?

2. Capitalization of expenditures to construct a tangible asset followed by depreciation, amortization, or cost recovery works more predictably than when expenditures are directed towards the “construction” of an intangible asset. Why do you think that this is so?

• Perhaps because a tangible asset physically deteriorates over time and so its useful life is more easily determinable.

3. Advertising and marketing campaigns: A marketing campaign requires current and future expenditures, but the “asset” it creates (consumer loyalty? brand recognition?) should endure past the end of the campaign. It is not even possible to know when this asset no longer generates income – as would be the case with an asset as tangible as, say, a building. A rational approach to depreciation, amortization, or cost recovery requires that we not only be able to recognize when an expenditure no longer generates income, but also be able to predict how long that would be.

• Consider expenditures for advertising. Not only do these problems emerge, but answers would be different from one taxpayer to the next.

4. The compliance costs of a rule that requires taxpayer to capitalize expenditures that generate income into the future can be enormous. At least one case was litigated all the way to the Supreme Court. Cf. Newark Morning Ledger Co. v. United States, 507 U.S. 546 (1993) (at-will subscription list is not goodwill and purchaser of newspaper permitted to depreciate it upon proof of value and useful life).

5. Perhaps there is something to be said for National Starch’s contention that capitalization required the “creation or enhancement of a separate and distinct asset.” Moreover, its statement in the third footnote (“absent a separate-and-distinct-asset requirement for capitalization, a taxpayer will have no ‘principled basis’ upon which to differentiate business expenses from capital expenditures”) just might be accurate. The Court dismissed this argument in the next sentence of the footnote by observing that the Court’s position essentially is no worse than taxpayer’s.

6. “Deduction rather than capitalization becomes more likely as the link between the outlay and a readily identifiable asset decreases, and as the asset to which the outlay is linked becomes less and less tangible.” Joseph Bankman, The Story of INDOPCO: What Went Wrong in the Capitalization v. Deduction Debate, in Tax Stories 228 (Paul Caron ed., 2d ed. 2009).

• “Deduction also becomes more likely for expenses that are recurring, or fit within a commonsense definition of ordinary and necessary.” Id.

7. Lower courts gradually began to read Lincoln Savings as requiring the creation or enhancement of a separate and distinct asset. Id. at 233.

• Nevertheless, the Supreme Court was correct in its reading of Lincoln Savings to the effect “that the creation of a separate and distinct asset well may be a sufficient, but not a necessary, condition to classification as a capital expenditure.”

8. On the other hand, does the Court announce that the presence of “some future benefit” is a sufficient condition to classification as a capital expenditure?

9. The INDOPCO holding called into question many long-standing positions that taxpayers had felt comfortable in taking. The cost of complete and literal compliance with every ramification of the holding would have been enormous. The IRS produced some (favorable to the taxpayer) clarifications in revenue rulings concerning the deductibility of certain expenditures. See Joseph Bankman, The Story of INDOPCO: What Went Wrong in the Capitalization v. Deduction Debate, in Tax Stories 244-45 (Paul Caron ed., 2d ed. 2009). In 2004, the IRS published final regulations. Guidance Regarding Deduction and Capitalization of Expenditures, 69 Fed. Reg. 436 (Jan. 5, 2004). The regulations represented an IRS effort to allay fears and/or provide predictability to the application of capitalization rules. In its “Explanation and Summary of Comments Concerning § 1.263(a)-4,” the IRS wrote:

The final regulations identify categories of intangibles for which capitalization is required. … [T]he final regulations provide that an amount paid to acquire or create an intangible not otherwise required to be capitalized by the regulations is not required to be capitalized on the ground that it produces significant future benefits for the taxpayer, unless the IRS publishes guidance requiring capitalization of the expenditure. If the IRS publishes guidance requiring capitalization of an expenditure that produces future benefits for the taxpayer, such guidance will apply prospectively. …

Id. at 436.

This positivist approach severely limits application of the “significant future benefits” theory to require capitalization of untold numbers of expenditures.

10. The “capitalization list” appears in Regs. §§ 1.263(a)-4(b)(1) and 1.263(a)-5(a).

• an amount paid to another party to acquire an intangible;

• an amount paid to create an intangible specifically named in Reg. § 1.263(a)-4(d);

• an amount paid to create or enhance a separate and distinct intangible asset;

• an amount paid to create or enhance a future benefit that the IRS has specifically identified in published guidance;

• an amount paid to “facilitate” (as that term is specifically defined) an acquisition or creation of any of the above-named intangibles; and

• amounts paid or incurred to facilitate acquisition of a trade or business, a change in the capital structure of a business entity, and various other transactions.

11. Moreover, Reg. § 1.263(a)-4(f)(1) states a 12-month rule, i.e., that

a taxpayer is not required to capitalize … any right or benefit for the taxpayer that does not extend beyond the earlier of –

(i) 12 months after the first date on which the taxpayer realizes the right or benefit; or

(ii) The end of the taxable year following the taxable year in which the payment is made.

12. When taxpayers incur recurring expenses intended to provide future benefits – notably advertising – what is gained by strict adherence to capitalization principles?

• In Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. v. Commissioner, 685 F.2d 212, 217 (7th Cir. 1982), Judge Posner wrote:

If one really takes seriously the concept of a capital expenditure as anything that yields income, actual or imputed, beyond the period (conventionally one year, [citation omitted]) in which the expenditure is made, the result will be to force the capitalization of virtually every business expense. It is a result courts naturally shy away from. [citation omitted]. It would require capitalizing every salesman’s salary, since his selling activities create goodwill for the company and goodwill is an asset yielding income beyond the year in which the salary expense is incurred. The administrative costs of conceptual rigor are too great. The distinction between recurring and nonrecurring business expenses provides a very crude but perhaps serviceable demarcation between those capital expenditures that can feasibly be capitalized and those that cannot be.

13. (Note 12, continued): Imagine: An author spends $5 every year for pen and paper with which to write books. Each book will generate income for the author for 5 years. Let’s assume that “the rules” permit such a taxpayer to deduct $1 of that $5 expenditure in each of the succeeding five years. This tax treatment matches the author’s expenses with his income. The following table demonstrates that this taxpayer will (eventually) be deducting $5 every year.

Beginning in year 5, how much does the year by year total change? Does this table suggest that there is an easier way to handle recurring capital expenditures than to require taxpayer to capitalize and depreciate every such expenditure?

14. You are expected to recognize a capitalization of intangibles issue – but the details of the regulations are left to a more advanced tax course.

C. Expense or Capital: Protecting Stock Investment or Protecting Employment

United States v. Generes, 405 U.S. 93 (1972)

MR. JUSTICE BLACKMUN delivered the opinion of the Court.

A debt a closely held corporation owed to an indemnifying shareholder employee became worthless in 1962. The issue in this federal income tax refund suit is whether, for the shareholder employee, that worthless obligation was a business or a nonbusiness bad debt within the meaning and reach of §§ 166(a) and (d) of the … Code112 and of the implementing Regulations § 1.166-5.113

The issue’s resolution is important for the taxpayer. If the obligation was a business debt, he may use it to offset ordinary income and for carryback purposes under § 172 of the Code … On the other hand, if the obligation is a nonbusiness debt, it is to be treated as a short-term capital loss subject to the restrictions imposed on such losses by § 166(d)(1)(B) and §§ 1211 and 1212, and its use for carryback purposes is restricted by § 172(d)(4). The debt is one or the other in its entirety, for the Code does not provide for its allocation in part to business and in part to nonbusiness.

In determining whether a bad debt is a business or a nonbusiness obligation, the Regulations focus on the relation the loss bears to the taxpayer’s business. If, at the time of worthlessness, that relation is a “proximate” one, the debt qualifies as a business bad debt and the aforementioned desirable tax consequences then ensue.

The present case turns on the proper measure of the required proximate relation. Does this necessitate a “dominant” business motivation on the part of the taxpayer, or is a “significant” motivation sufficient?

Tax in an amount somewhat in excess of $40,000 is involved. The taxpayer, Allen H. Generes, prevailed in a jury trial in the District Court. On the Government’s appeal, the Fifth Circuit affirmed by a divided vote. Certiorari was granted to resolve a conflict among the circuits.

I

The taxpayer, as a young man in 1909, began work in the construction business. His son-in law, William F. Kelly, later engaged independently in similar work. During World War II, the two men formed a partnership in which their participation was equal. The enterprise proved successful. In 1954, Kelly Generes Construction Co., Inc., was organized as the corporate successor to the partnership. It engaged in the heavy-construction business, primarily on public works projects.

The taxpayer and Kelly each owned 44% of the corporation’s outstanding capital stock. The taxpayer’s original investment in his shares was $38,900. The remaining 12% of the stock was owned by a son of the taxpayer and by another son-in law. Mr. Generes was president of the corporation, and received from it an annual salary of $12,000. Mr. Kelly was executive vice-president, and received an annual salary of $15,000.

The taxpayer and Mr. Kelly performed different services for the corporation. Kelly worked full time in the field, and was in charge of the day-to-day construction operations. Generes, on the other hand, devoted no more than six to eight hours a week to the enterprise. He reviewed bids and jobs, made cost estimates, sought and obtained bank financing, and assisted in securing the bid and performance bonds that are an essential part of the public project construction business. Mr. Generes, in addition to being president of the corporation, held a full-time position as president of a savings and loan association he had founded in 1937. He received from the association an annual salary of $19,000. The taxpayer also had other sources of income. His gross income averaged about $40,000 a year during 1959-1962.

Taxpayer Generes from time to time advanced personal funds to the corporation to enable it to complete construction jobs. He also guaranteed loans made to the corporation by banks for the purchase of construction machinery and other equipment. In addition, his presence with respect to the bid and performance bonds is of particular significance. Most of these were obtained from Maryland Casualty Co. That underwriter required the taxpayer and Kelly to sign an indemnity agreement for each bond it issued for the corporation. In 1958, however, in order to eliminate the need for individual indemnity contracts, taxpayer and Kelly signed a blanket agreement with Maryland whereby they agreed to indemnify it, up to a designated amount, for any loss it suffered as surety for the corporation. Maryland then increased its line of surety credit to $2,000,000. The corporation had over $14,000,000 gross business for the period 1954 through 1962.

In 1962, the corporation seriously underbid two projects and defaulted in its performance of the project contracts. It proved necessary for Maryland to complete the work. Maryland then sought indemnity from Generes and Kelly. The taxpayer indemnified Maryland to the extent of $162,104.57. In the same year, he also loaned $158,814.49 to the corporation to assist it in its financial difficulties. The corporation subsequently went into receivership and the taxpayer was unable to obtain reimbursement from it.

In his federal income tax return for 1962 the taxpayer took his loss on his direct loans to the corporation as a nonbusiness bad debt. He claimed the indemnification loss as a business bad debt and deducted it against ordinary income.114 Later, he filed claims for refund for 1959-1961, asserting net operating loss carrybacks under § 172 to those years for the portion, unused in 1962, of the claimed business bad debt deduction.

In due course, the claims were made the subject of the jury trial refund suit in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana. At the trial, Mr. Generes testified that his sole motive in signing the indemnity agreement was to protect his $12,000-a-year employment with the corporation. The jury, by special interrogatory, was asked to determine whether taxpayer’s signing of the indemnity agreement with Maryland “was proximately related to his trade or business of being an employee” of the corporation. The District Court charged the jury, over the Government’s objection, that significant motivation satisfies the Regulations’ requirement of proximate relationship.115 The court refused the Government’s request for an instruction that the applicable standard was that of dominant, rather than significant, motivation.116

… [T]he jury found that the taxpayer’s signing of the indemnity agreement was proximately related to his trade or business of being an employee of the corporation. Judgment on this verdict was then entered for the taxpayer.

The Fifth Circuit majority approved the significant motivation standard so specified and agreed with a Second Circuit majority in Weddle v. Commissioner, 325 F.2d 849, 851 (1963), in finding comfort for so doing in the tort law’s concept of proximate cause. Judge Simpson dissented. 427 F.2d at 284. He agreed with the holding of the Seventh Circuit in Niblock v. Commissioner, 417 F.2d 1185 (1969), and with Chief Judge Lumbard, separately concurring in Weddle, 325 F.2d at 852, that dominant and primary motivation is the standard to be applied.

II

A. The fact responsible for the litigation is the taxpayer’s dual status relative to the corporation. Generes was both a shareholder and an employee. These interests are not the same, and their differences occasion different tax consequences. In tax jargon, Generes’ status as a shareholder was a nonbusiness interest. It was capital in nature, and it was composed initially of tax-paid dollars. Its rewards were expectative, and would flow not from personal effort, but from investment earnings and appreciation. On the other hand, Generes’ status as an employee was a business interest. Its nature centered in personal effort and labor, and salary for that endeavor would be received. The salary would consist of pre-tax dollars.

Thus, for tax purposes, it becomes important and, indeed, necessary to determine the character of the debt that went bad and became uncollectible. Did the debt center on the taxpayer’s business interest in the corporation or on his nonbusiness interest? If it was the former, the taxpayer deserves to prevail here. [citations omitted.]